Sombre, but still arrestingly grand.Ĭhristine Riding, head of the National Gallery’s curatorial department, believes the institution is the perfect forum for Wiley’s work.

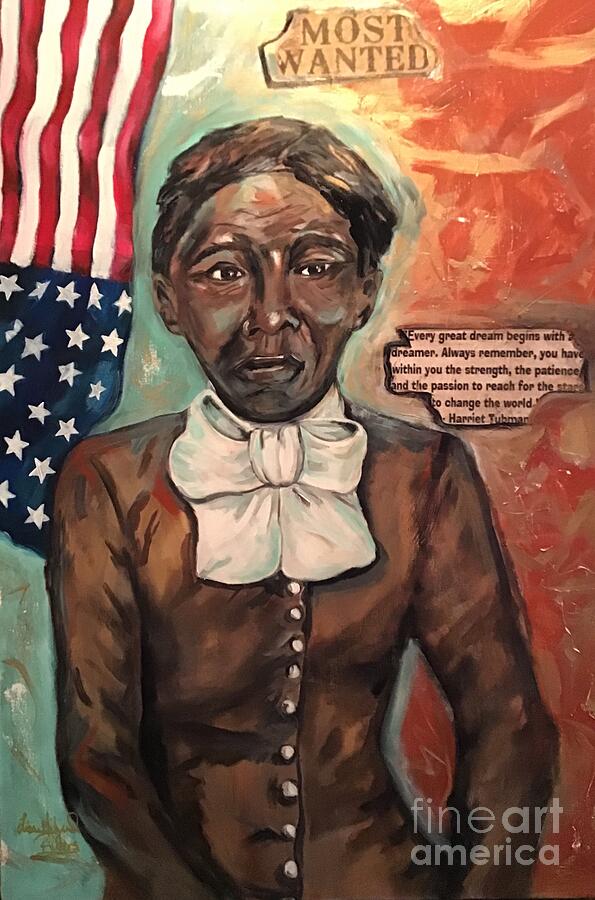

Set in the fjords of Norway, these new paintings are muted in tone and hue. Inspired by Romantic landscapes and seascapes in the gallery’s collection by painters including Claude Lorrain, Caspar David Friedrich, JMW Turner, and Claude-Joseph Vernet, six new works (five paintings and one film) will still feature the emblematic Black figures, but the style will mark a dramatic departure from his kaleidoscopic portraits, with their lively brocade backdrops and vibrant pigments. We are on the call to talk about Wiley’s move into landscape painting for his latest show, The Prelude, which opens at the National Gallery next month. “ busy but good,” he says, sounding exhausted but smiling widely. There’s a sense of urgency in the air as he’s conducting several interviews back to back. He’s at the SoHo Grand Hotel and has just finished his Observer photoshoot. Speaking over Zoom from New York, Wiley appears in a good mood. Wiley draws out complex historical and contemporary issues – race, identity, climate – with such power and poignancy Christine Riding, National Gallery “It’s an opportunity for people who traditionally have had very little relationship to museums and to what’s on their walls, to feel themselves included,” he says. In a similar way to other African American artists such as Kerry James Marshall, Amy Sherald and Jordan Casteel, Wiley’s work inserts Black faces into historical white spaces and thus also into the canon of painting. While he is famed for painting celebrities and cultural figures, from Spike Lee to LL Cool J, Questlove to Ice-T (his best known work is his 2018 portrait of Barack Obama, sitting relaxed on a wooden chair and surrounded by an abundance of leafy flowers), his work is just as likely to feature ordinary Black people he has found by scouring the local neighbourhoods. His subversion of the conventions of the medium often involved creating pastiches that foreground Black youth and hip-hop culture and fashion his works include remakes of Napoleon Crossing the Alps, by Jacques-Louis David, Jacob de Graeff by Gerard ter Borch and The Dead Christ in the Tomb by Hans Holbein the Younger. His brightly coloured work is easy to identify: glowing brown skin, statuesque poses, richly patterned, often floral, backgrounds and a roster of unfamiliar but photogenic faces. Wiley, 44, beloved by hip-hop superstars, signed to a Hollywood talent agency, and the first Black, gay artist to paint a US president’s official portrait, rose to art world fame in the 2000s for reimagining such classic European paintings with Black protagonists. “What I wanted to do was to take the good parts, the parts that I love, and fertilise them with things that I know to be beautiful – people who happen to look like me.”

Such paintings, from the baroque, rococo, renaissance and Dutch golden age eras, are ultimately displays of European power, wealth, and beauty. Something beautiful in those expansive imperialist landscapes.” But there’s a dead end. “There’s something glorious about the portraits that you see of aristocrats and royal families. Kehinde Wiley has a love-hate relationship with western art history.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)